|

|

Effectiveness

monitoring is the process of identifying and measuring key indicators

of ecosystem response to a restoration treatment (Machmer and Steeger

2002). Monitoring is essential to an adaptive management approach

to restoration, as it assesses progress towards your goals and objectives.

It also enables you to improve your restoration techniques and their

cost effectiveness. Without monitoring, there is a tendency to repeat

treatments without questioning their efficacy, or their applicability

to different biogeoclimatic zones (Clewell and Rieger 1997). In

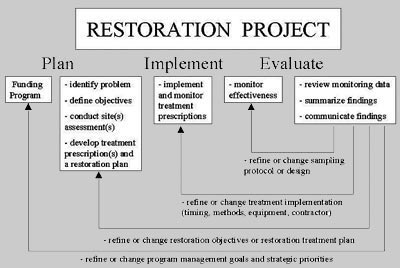

other words, without monitoring you can't tell what works. Figure 1. The following is taken from Machmer and Steeger (2002), and illustrates the role of effectiveness monitoring within an adaptive management framework for ecosystem restoration

Effectiveness monitoring differs from implementation monitoring, which answers the question of how well the treatments were carried out relative to a restoration prescription (Machmer and Steeger 2002). Implementation monitoring is discussed in a previous section. Effectiveness monitoring can be carried out at different levels of intensity, depending on the complexity and scale of your restoration project. Routine evaluations are the kind that most readers of this guide will undertake. Routine evaluation will apply to restoration projects with relatively straightforward objectives and established methods, which are applied to a relatively small area over a relatively short time period. This type of evaluation involves quick data collection at low cost, using mainly qualitative methods, including photo points, visual estimates, or rating systems, to compare one or a few key response variables before and after restoration. This method will also serve to identify areas where more detailed evaluation is required. An example of a routine level of effectiveness monitoring would be in a project involving noxious weed removal. Monitoring the effectiveness of the weed removal might entail qualitatively assessing weed and native species vegetation cover through pre- and post-treatment photographs taken at permanent photo-points. In some cases, a low level quantitative assessment might be warranted: for example, measurement of percent cover and weed species density in sampling plots along a random transect (Machmer and Steeger 2002).

Intensive

evaluation involves taking quantitative

data over a longer time period, and is generally more expensive

(Machmer and Steeger 2002). An intensive evaluation would be used

only for selected projects, for individual sites that are part of

a larger 'program', or in critical parts of projects, for example,

where the success of the establishment of rare species is an essential

restoration goal. Intensive evaluation would be necessary when applying

a restoration treatment over a large area, when using new or weakly

documented techniques, or when several treatments are involved and

you wish to discern their individual and collective effects. Such

an evaluation provides a quantitative measurement of pre- and post-treatment

site condition, and ecosystem recovery is based on the measurement

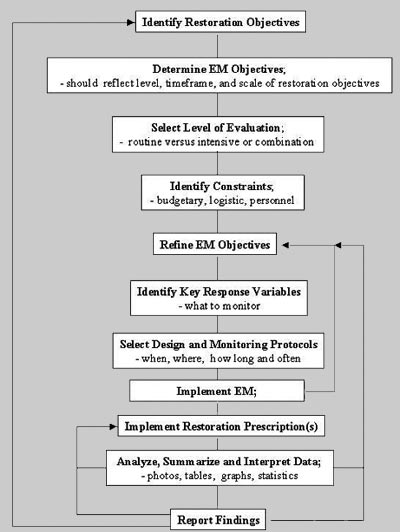

of several key response indicators (Machmer and Steeger 2002). Figure 2. Steps in Effectiveness Monitoring, from Machmer and Steeger (2002), adapted from Gaboury and Wong (1999).

It will be important to share your monitoring findings in progress reports, anecdotally, and at conferences and in publications. All data should be stored in both hard copy and electronic form in a manner that makes it easy to share with others. You will want to make this data available to people that may learn from or eventually take over the restoration program. You can check with FORREX (www.forrex.org), for ways of disseminating your findings to other practitioners in BC.

Appendix 3 contains an example outline for drawing up a monitoring plan. Monitoring must be built into your restoration plan schedules and budgets. Some forms of monitoring will not be complete until years or decades into the future, and you must document your monitoring needs and procedures, and share your monitoring plans and data. |

||||

|

|||||

|

|

|||||