|

|

Establishing Desired Future Condition Desired future condition (DFC) is a

commonly used term for describing a restoration goal, or end-point.

The desired future condition may be an ecosystem that functions

and looks like it did historically, before it was disturbed. In

contrast, the DFC may describe a new reality that takes into account

human presence and impacts that cannot be redressed. For example,

exotic species and roads may never be removed from some ecosystems,

but it is possible to reduce or limit their numbers or extent. Conversely,

certain large predators or rare plants and animals may never be

restored to some ecosystems, so the DFC would describe a relatively

healthy ecosystem that is missing some of its former diversity. Using Reference Ecosystems Undisturbed

or less disturbed contemporary "reference" areas and historical

landscape descriptions can be used in the development of restoration

goals. Plant, animal, soil, and water data from these reference

ecosystems provide useful "templates" for restoration

work in similar sites (Gayton 2001). The potential and problems

of using both contemporary and historical reference area information

are discussed here in turn. The serious restoration practitioner

should always consult a number of historical and contemporary sources

before constructing a template for restoration (Gayton 2001). Using Contemporary Reference Conditions as Templates Ecological Reserves, Wildlife Management Areas, Parks, Protected Areas, Rangeland Reference Areas, and other relatively undisturbed sites, on both public and private land, can act as sources of restoration information (Gayton 2001). However, European influence on our ecosystems has been so pervasive that undisturbed areas are rarely found, particularly in zones of level, fertile land, in riparian communities, and near populated areas where restoration projects most often occur. Because reference areas are frequently small parcels, surrounded on all sides by early successional and disturbed lands, they are usually not fully representative of "pristine" ecosystems because of edge effects, invasion by introduced or undesirable native species, or "overrest" (too little natural disturbance), yet they still offer many useful clues. For example, at a Rangeland Reference Area near the East Kootenay community of Skookumchuck, even though the biodiversity and vigour of many species of grasses and herbs has increased inside the protected area, the accumulation of grass litter over the past fifty years has allowed for the establishment of a Ponderosa pine forest inside the exclosure. Normally the combined action of ungulate grazing and frequent fire on this dry site would not permit the establishment of a forest (Gayton 2001).

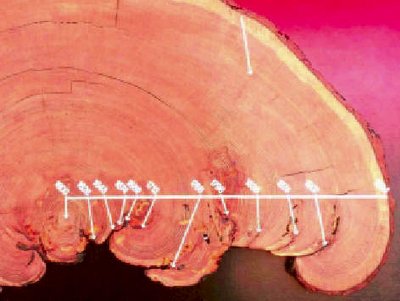

Using Historical Reference Conditions as Templates Another common reference point for ecological restoration is the way an ecosystem appeared to function historically (Gayton 2001). Such historical benchmarks are generally selected from within our modern climatic period, but before significant European influence. In British Columbia, this period is from about 1600 to 1880, and in some very remote areas this period may even extend to the present. Early published accounts, old-timers' recollections, early research projects, First Nations' accounts, archival photographs, tree rings, pollen cores, and fire scars are typical sources of data for this era, but many others are available to the creative investigator (Gayton 2001). Older air photos also add to an understanding of the site, though these generally date back only to the 1950s.

No single historical data source will be definitive. Historical

journals and archival photographs can depict landscapes during atypical

weather conditions or unusual disturbance events. Narrow, site-specific

information and incomplete memory can skew historical observations.

The restorationist must also guard against his or her own subjectivity

when reviewing historical sources (Gayton 2001). |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||