|

|

Developing

Prescriptions

Final restoration objectives can now be set,

based on the site survey and maps. Your prescriptions should take

the form of maps showing the treatment locations, accompanied by the

rationale for treatment, descriptions of treatments, and treatment

schedules and costs (see Restoration Plan example, Appendix

1). Restoration prescriptions will also include future maintenance

and monitoring requirements, and will take into account safety and

other logistical concerns.

Some considerations common to many projects are listed below.

In a world of limited funding, it is important to prioritize treatments;

for example, present each site or prescription type in terms of high,

medium, and low priority. At the stage of prescription development,

it is also wise to involve key players (see below).

It's important to note that prescribing no treatment is often a valid

option - either because the ecosystem is healing itself satisfactorily,

or because the problem is too difficult or expensive to fix.

| Checklist for Prescription

Development |

| |

Good Restoration Prescriptions Are:

- Cost effective

- Likely to succeed

- High priority

- Reasonable in maintenance requirements

- Approved by key players

|

Involving Key Players in Prescription

Development

Using Experts

Most restoration projects require professional

advice in the planning and prescription development stages. An appropriate

specialist can usually be found by asking key

players, or by making inquiries to the BC

Chapter of The Society for Ecological Restoration.

Involving Stakeholders

Government, First Nations, commercial interests,

or other key players will

often have some say in what happens, and for prescription development

you will need their buy-in. The best way to solicit input is to

have these parties visit the site before the plans are finalized.

It is at this stage that you can get technical input and future

commitments to your plans, often for free.

The local community may also need to play a role or be educated

about the restoration project. An example of the need to involve

the community is where community viewscapes or recreation opportunities

will be affected, or where there is a perception of risk to private

property. The importance of community buy-in cannot be overemphasized

on these types of sites, as an uninformed and unhappy public can

successfully oppose your restoration plans. Another important reason

for community education is to create potential volunteers that may

lend a hand to your efforts, and assist in stewardship and monitoring

in years to come.

Common Restoration Considerations

Some special considerations must be taken into account, depending

on your site and project. Table 5 lists some common considerations,

which are also explained individually below.

Planting Prescriptions

Planting trees, shrubs, or grasses is part of many restoration projects.

It is important to consider the timing of planting, type of planting

stock, and hazards to the planted stock, such as drought or disturbance

by animals. The specific timing of planting will depend on your

region, but it is generally in spring or fall, when there is enough

moisture to allow the plants to establish. In particularly vulnerable

areas, irrigation, though expensive, may be the only way of ensuring

survival through the summer months.

Choosing the right type and size of plant stock is important to

help ensure the plant's survival. Local plant stock should be used

whenever possible, because it may have attributes that will help

it survive better. Using local stock is easiest when the project

involves using deciduous cuttings or "whips" (e.g., dogwood,

willow, or cottonwood) that can be collected from nearby sites,

as long as care is taken not to overharvest the source populations.

Local native vegetation is rarely available in quantity from nurseries

without special ordering, thus it may take advance planning to collect

and grow local trees, shrubs and herbs, something your local nursery

can do if given enough notice. Generally, a lead time of two or

three years will be required to collect seed and grow the plants

to sufficient size. If you are time-limited and wish to purchase

standard trees from a nursery, you will usually obtain different

stock than would exist in your area, though controls exist in BC

to ensure that tree seedlings are ecologically appropriate for the

general region. In general, the largest possible tree stock should

be used, in order to maximize survival and minimize maintenance.

Dave Polster

Contracting with a nursery to grow the

plants you need is an effective way of ensuring the right materials

are available.

On barren, disturbed sites

where erosion control is the objective, you may decide to seed grasses

and legumes for quick ground cover. However, native grass seed mixes

are not commercially available at present, though several projects

are underway to improve this situation. Restorationists should be

on the lookout for native seed options as they develop. Another

consideration for grass seeding is the avoidance of dense, sod-forming

species in the wetter zones of the province. Dense grass sod can

out-compete planted trees, exclude later seral species from establishing,

and harbour rodent populations that will girdle trees. Your seed

supplier will be able to exclude or balance the sod-forming species

in your seed mix, upon request.

Once the trees or shrubs are planted, you often need to protect

them from animals. You'll need to make inquiries about the risk

of animal damage in your area, and monitor your planted stock closely

to make sure you are not simply providing animal food. Deer browsing

is a big problem in most areas, and protective tree covers are commercially

available to allow trees to attain heights where deer are less interested

in browsing. Trees planted in grassy areas are prone to girdling

from rodents, and rabbits will also girdle trees. If you are planting

cuttings near a beaver dam you can expect the beaver to take some,

and should think about a fence to exclude the beaver.

Trees and shrubs should be planted at densities higher than the

final target, to account for mortality due to animals, disease,

and drought. Once trees are well-established, thinning may be necessary

in order to establish a tree density appropriate for the site.

Dave Polster |

Dave Polster |

| Grazing animals can severely damage

planted stock. |

Planting programs must be conducted

when the conditions are optimum for plant growth. Avoid times

when the newly planted materials will be stressed due to lack

of moisture. |

Invasive Species

There are many invasive non-native species,

both plant and animal, that are a major restoration concern in British

Columbia. Many restoration projects simply attempt to control the

invasive species to allow native ecosystems to re-establish. For

example, much effort goes into Scotch broom eradication on eastern

Vancouver Island, and knapweed control in the dry interior. Restoration

efforts may also open up an area to problem invasive plants by disturbing

soil or increasing light availability. Restorationists must take

care to not make the problem worse.

Dave Polster

The effects of Scotch broom removal on Garry

oak communities can be dramatic, as seen in these before (left)

and after (right) photos taken 5 years apart in the same general

area.

Invasive exotic species are

highly competitive and are difficult to eradicate, as they lack

the predator, competitor and disease controls from their native

environments. Many weedy plant species produce large numbers of

seeds that can persist in the soil for decades. The long-term presence

of these invasive weeds and animals degrades ecosystems through

competition, exclusion, and predation on native plants and animals.

While eradication of all but the most recent arrivals isn't likely,

with vigilance and effort their numbers can be controlled.

In previously forested environments, establishing fast-growing native

trees and shrubs will usually shade out the light-requiring exotics.

For example, red alder, willow, dogwood, and cottonwood can be used

on the coast to shade out problem species like reed canarygrass

and blackberry, and re-establishing Douglas-fir forests will eliminate

Scotch broom.

In many places in the dry interior the weed problem is severe. Biological

controls are used for some of these species, and should form part

of a restoration program in areas where they can be applied. Other

methods of control are hand-pulling, mowing, or in special cases,

using herbicides.

| Herbicides |

| Herbicides are used to control unwanted vegetation, like

exotic weeds. However, in ecological restoration projects they

are not usually the method of choice, as they may kill native

species or lead to other problems in the ecosystem. The ability

of herbicides to be selective is related to a higher tolerance

of the poison by some species compared to others. Some authors

believe that using herbicides creates a disturbance into which

weeds invade, thereby worsening the problem (Polster and Landry

1993). Where herbicides are chosen to control problem weeds,

follow-up monitoring will be necessary to discern whether they

are having their intended effect. |

Dave Polster

Mowing can be an effective strategy for control

of some unwanted invasive plants as it can remove the seed portion

of the plant, impeding the plant's ability to propagate.

Information on managing invasive plant species

may be obtained from a variety of resource agencies as well as private

groups such as the Cattleman's Association. Information on control

of some specific invasive species can be obtained from researchers

at universities as well as Ministry of Forests research stations

throughout the province. However, as much information as there is

on the control of weeds, there is relatively little information

on the management of invasive species in the context of ecosystem

restoration. Adopting treatment methods that are used in agriculture

or forestry may be inappropriate within the context of ecological

restoration. Developing a strategy for environmentally sensitive

management of invasive species requires careful consideration of

the ecological consequences of the various potential management

techniques.

Species At Risk/

Species Needing Special Management

Even when your restoration project is addressing ecosystem or habitat-related

restoration needs, single species are usually a consideration. You

should have identified any species of concern early in your information-gathering

phase (see 'Gathering Information

and Data'). At the very least, your plans should ensure that

you will not harm species at risk, and ideally your restoration

program should attempt to restore both the species and its native

ecosystem.

Working with rare and endangered 'species at risk' will require

agency buy-in. If your plans include restoration of rare plants,

the Native Plant Society of BC can also provide advice on your strategy,

and guidelines to avoid damaging limited populations through collection

of seeds or plant parts. (Contact information for the Society can

be found at: http://www.vcn.bc.ca/npsbc/).

Dave Polster

The yellow montane violet (Viola praemorsa)

is a species at risk in the Garry oak ecosystems of SE Vancouver

Island. Restoration efforts in these ecosystems must ensure that

these important ecosystem elements are not lost.

Many species that are not

officially 'at risk' may also require special consideration

in your plans,

due to specific habitat needs that wouldn't otherwise be met, possible

impacts to their habitat caused by your restoration project,

or

because of their importance to the ecosystem. For example, certain

species use tree cavities to nest, roost, and feed, and populations

of these species are generally depressed or absent due to a lack

of adequate habitat. Second growth forests, even when thinned

in

order to develop old-growth characteristics, will lack these cavity

features for decades. Techniques are under development to create

cavities and rot in trees, and using these techniques is an example

of the fine-filter approach

to restoration, within the context of stand-level (coarse-filter)

treatments like thinning and fire. If you require information about

individual species in your ecosystem, your regional office of the

Ministry of Environment may be able to help.

Values at Risk

Restoration work may involve risk to ecological values or species

at your site, as well creating risk to property values. As part

of your planning process you should ensure that any risk is warranted

and mitigated. Getting the proper permits, making detailed plans,

and consulting with the community will lower your liability and

your risk.

An obvious example of managing risk is with fire-supported restoration.

If you plan to do a prescribed burn, you will need to manage risk

to organisms and habitat features on the site, as well as ensure

that your fire doesn't escape and damage property. Other options

besides fire will need to be explored when the risk or consequence

of failure is too high.

Soil Rehabilitation

If you have reason to believe the soils on your site have been altered

and will not support your desired vegetation, you may have to address

soil compaction or lack of nutrients and organic materials as one

of your first restoration activities. Without the proper soil conditions,

your desired plant community may not become established.

Chuck Bulmer

Soil ripping is an important part of soil rehabilitation

where soil compaction is a problem, such as on roads and landings

where heavy equipment has operated.

If your site was used for industrial

or urban activities, soil compaction caused by heavy machinery may

inhibit plant growth. "Ripping" old roads and landing

sites might be required to loosen up the ground for growing plants.

Industrial areas also tend to suffer from the removal of topsoil.

Chemical fertilizers or organic mulch can be used, and sometimes,

the planting of nitrogen fixing plant species such as legumes and

alder is useful. Adding old logs and stumps (coarse

woody debris) to the soil surface will help the area

recover moist microsites and organic material, and may speed up

recovery of the ecosystem. These activities might be enough to start

the process of succession. Comparison with a reference ecosystem

will help illustrate the appropriate chemical and physical goals

for your degraded soils.

Methods used to reclaim mine sites must be used with caution in

ecological restoration. Soil amendments like manure and biosolids

can alter natural soils and may introduce foreign materials to your

site.

The Forest

Practices Code Soil Rehabilitation Guidebook (Province of BC

1997) provides a good discussion of all types of soil rehabilitation

in BC. This and other guidebooks are available for purchase through

the Crown Publications Index: www.publications.gov.bc.ca.

Slope Instability/

Bioengineering

Unstable areas can remain unvegetated for years. When the source

of the instability is below the surface, devastating landslides

can result. Most slope instability is caused by forestry or mining

access roads, where older techniques of road building have created

unstable 'fill' slopes, steep 'cut' slopes, and harmful drainage

pathways. It is important to consult an experienced geoscientist

in cases of slope instability. In addition, when addressing instability

as part of an ecological restoration project, you will need to give

special consideration to the types of plant material used to revegetate

the area.

Road and hillslope related rehabilitation is discussed in detail

in the publication "Best Management Practices Handbook: Hillslope

Restoration in British Columbia. Watershed Restoration Technical

Circular No. 3 (revised), (Atkins et al. 2000). This publication

is available from the Ministry of Forests: http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/RTE/engineering/wrp-pub.htm.

Surface instability can be treated very effectively with soil bioengineering

techniques, where live materials are used to create physical stability.

Growth of these materials allows the process of succession to begin.

See Polster (2001) for more information on using bioengineering

techniques in restoration. Bioengineering courses are offered through

the Forestry Continuing Studies Network (see Resources section.)

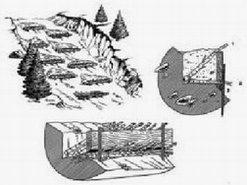

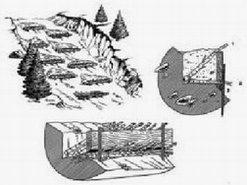

| Common Bioengineering

Techniques |

Dave Polster |

Dave Polster |

| Modified brush layers are used on steep

ravelling slopes to stop the rolling stones and allow vegetation

to establish. The cuttings are placed above the board on moderate

sites (1), on dry sites they are placed below the board (2),

while on wet sites a small wattle fence is built below the board

(3). |

Live reinforced earth walls are used

where slumping has resulted in a cavity in the slope. Backfill

comes from shaving the slope above the cavity. |

Cost Effectiveness

Restoration dollars are always at a premium.

Hence, cost-effectiveness should always be explored, and treatments

must be prioritized based on need and on the benefit relative to

the cost. Often, operational trials can be done to explore whether

cheaper methods yield acceptable results. More expensive techniques

don't necessarily translate into improved performance. An example

is establishing trees like red alder: nursery-grown trees are expensive

to buy and plant, and direct seeding may provide a reasonable alternative

at a fraction of the cost (Warttig and Wise 1999). Restoration techniques

that work with natural processes like succession will be the most

cost effective, and the most likely to succeed.

Including Maintenance in your Restoration

Prescriptions

Maintenance is so important to restoration that a section is devoted

to it later in these guidelines (see 'Maintenance').

However, mention is also warranted here. Maintenance needs will

determine the cost effectiveness and feasibility of a prescription,

and these needs must be considered when choosing the appropriate

prescriptions to implement. Good restoration prescriptions will

include maintenance in the budget and schedule of activities.

|